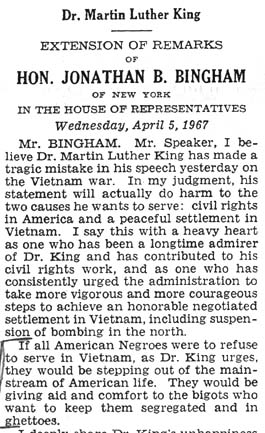

"Extension of Remarks of Hon. Jonathan B. Bingham of New York

in the House of Representatives"

"Extension of Remarks of Hon. Jonathan B. Bingham of New York

in the House of Representatives"

Wednesday, April 5, 1967

Congressional Record 113, Part 7, H8497.

FULL TEXT FULL TEXT

MR. BINGHAM. Mr. Speaker, I believe Dr. Martin Luther King has made a

tragic mistake in his speech yesterday on the Vietnam war. In my judgment,

his statement will actually do harm to the two causes he wants to serve:

civil rights in America and a peaceful settlement in Vietnam. I say this

with a heavy heart as one who has been a longtime admirer of Dr. King and

has contributed to his civil rights work, and as one who has consistently

urged the administration to take more vigorous and more courageous steps

to achieve an honorable negotiated settlement in Vietnam, including

suspension of bombing in the north.

If all American Negroes were to refuse to serve in Vietnam, as Dr. King

urges, they would be stepping out of the mainstream of American life.

They would be giving aid and comfort to the bigots who want to keep

them segregated and in ghettoes.

I deeply share Dr. King's unhappiness that vital domestic programs aimed

at wiping out poverty and assuring equal rights for all are suffering

because of the fiscal demands of the Vietnam conflict. That is one of

many reasons why I desperately want to see a speedy end to the conflict.

But such a speedy end cannot be achieved by military action, and it cannot

be achieved by a U.S. withdrawal because such an abandonment of U.S.

commitments is as a practical matter out of the question. It can only

come, therefore, through negotiation.

The tragedy is that a statement like Dr. King's represents a setback for

the possibility of meaningful negotiations. Coming as it did on the heels

of Hanoi's rejection of U Thant's cease-fire proposals, which had been

substantially accepted by the United States and South Vietnam, Dr. King's

speech can only be interpreted by Hanoi as approval of its intransigent

stand. Accordingly, Hanoi will be encouraged to continue to believe that

if it goes on refusing either a mutual cease-fire or negotiations,

eventually the United States will get tired of it all and quit.

This is a mistaken conclusion, I am sure, but apparently Hanoi believes

it.

Dr. King's five-point program, while containing some sound proposals, is

in other respects wholly unrealistic. He urges, for example:

The declaration of a unilateral cease-fire in the hope that such action

would create an atmosphere for negotiation.

He does not say what course he would favor if his "hope" were not realized

and a bilateral cease-fire and negotiations did not follow, and if a firm

date for U.S. withdrawal had also been set, as he further proposes, Hanoi

would have no incentive whatever to cease firing and negotiate.

As reported in the New York Times, Dr. King's description of what is

happening in Vietnam is fearfully one sided and distorted. There was

apparently no mention of the important steps recently taken in South

Vietnam in the direction of constitutional and representative government;

no mention of the constructive civil programs being carried on in South

Vietnam by dedicated and courageous Americans of all races; no mention of

Hanoi's consistent rejection of peace overtures made by U Thant, the Pope,

and President Johnson. His description, which is not based on firsthand

observation but on secondhand reports, appears to proceed on the theory

that the information presented by the other side's propagandists is

accurate. He virtually ignores not only all information furnished by

the American Government, but also what has been reported by most American

and foreign correspondents in South Vietnam.

Finally, I believe that Dr. King is cruel in telling American Negro

fighting men in Vietnam that they are the victims of discrimination.

I am reliably informed that Negroes are being drafted into our Armed

Forces today in almost exactly the same ratio to whites as obtains in

the U.S. population, about 11 percent. The reason the proportion of

Negroes in the fighting forces in Vietnam is higher than that is because

of a very high reenlistment rate among Negroes.

One last point needs to be made: While it is true that the slowdown in

antipoverty and other urban programs caused by the Vietnam conflict is

hurting disadvantaged Negroes, it is also hurting, without discrimination,

other disadvantaged groups in the population, including the hard-pressed

aged, the handicapped, the undereducated children, the unskilled poor, the

slum dwellers. Many of these are Negro, but more are not.

|